Ghana’s Movie Industry

Film in much of Africa is a field that remains largely unknown to many people in Europe. While some South African films such as “The Gods Must Be Crazy” and “District 9” have also been commercially successful, and some cinephiles may be familiar with Senegalese productions such as “La noire de...” and “Touki Bouki,” which also appear on European-influenced critics' lists, the national film industries of other countries are far less well known. English-speaking Africa is dominated by Nigeria's ecosystem, also known as “Nollywood”; only Bollywood produces a larger number of films annually. Given the linguistic and geographical proximity and Nigeria's much larger domestic market, it is not surprising that the names of Ghanaian actors often appear on the posters of Nigerian films. Nevertheless, film as an art form also has an exciting and often eventful history in Ghana itself, which we would like to share with you in this article.

The Beginnings of Ghana’s Film Industry

In 1964, a few years after Ghana gained independence under Kwame Nkrumah, the Ghana Film Industry Corporation was founded with the aim of educating and enlightening the population – albeit in line with the increasingly authoritarian government. After Nkrumah was overthrown just two years later, the GFIC gradually lost its monopoly on film production and distribution. It was not until the 1980s that film in Ghana experienced a resurgence with the emergence of independently financed projects. One of the earliest is Kwaw Ansah's “Love Brewed in the African Pot” from 1981.

Love Brewed in the African Pot was one of Ghana's first commercially and critically successful independent films and is considered a classic of West African cinema. With its story about a failing couple during the colonial period, it also stands as an example of the political commitment of the artistic generation around Kwaw Ansah.

An anecdote about its production illustrates how precarious film financing was in these times: Ansah had to put up his father-in-law's house as collateral for the bank loan. Despite these adversities, the film was one of the first to receive international acclaim, winning the UNESCO Film Prize. Ansah follows in the pan-African tradition of Nkrumah, and his film accordingly deals with typical themes such as class conflicts and the tension between European and African values in the context of a young couple in love during the colonial era whose marriage is not approved of due to the class difference. His later film “Heritage Africa” also discusses Ghana's past through the example of a civil servant in the Ghanaian colonial administration who renounces his African heritage in the hope of social advancement.

Alongside Ansah, King Ampaw is considered one of the founders of independent Ghanaian cinema. Ampaw's career shows a different approach to Ghana's colonial heritage; as a graduate of the Munich Film Academy, he also appeared as an actor in Werner Herzog's “Cobra Verde” and considers his style to be influenced by Jean-Luc Godard. His film Kukurantumi: Road to Accra (1983), about a bus driver who commutes figuratively and literally between the village of Kukurantumi and the capital Accra, was financed by a German broadcasting station and was one of the first Ghanaian films to be shown on European television.

The Video Film Era

During the 1980s, Ghana experienced an innovation that was also to fundamentally change Nigerian cinema at the same time: expensive film cameras were replaced by video cameras, which massively reduced production costs and significantly increased the number of films being made. This development in Ghana began with William Akuffo's “Zinabu” (1985), which deals with a witch's conversion to Christianity and, typical of this genre, the conflict between traditional and Christian religion. The effects of this “video film era” are mixed: while it has made film accessible to many Ghanaians through inexpensive cassettes, the production conditions for the actors are often hardly acceptable and the quality of the individual films varies greatly.

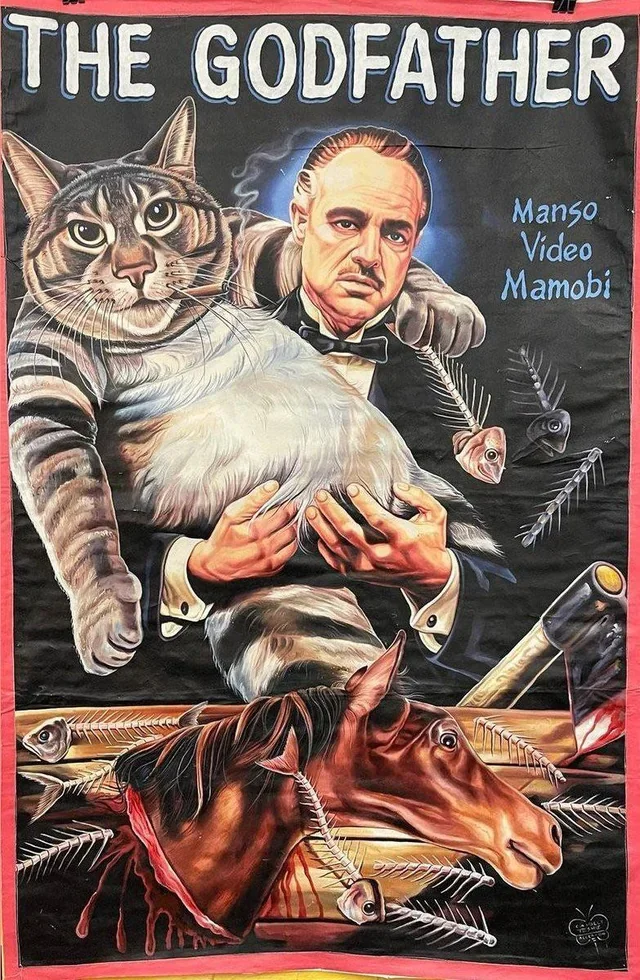

The abundance of low-budget films soon led to the emergence of small, often mobile cinemas, especially in the Accra region. This was accompanied by a typically Ghanaian style of hand-painted movie posters, which present the advertised movie's contents with varying faithfulness. These have since achieved cult status: some of the poster artists still receive commissions for new posters of Hollywood classics in this distinctive style.

In the 1980s, Ghanaian cinemas were often but a projector and a generator that were transported from place to place in a small van. To promote their offer, the owners commissioned hand-painted posters. The advertising effect was often more important than a truthful representation of the film's content.

Cinema in modern day’s Ghana

While English-language films dominated Ghana's output for a long time, an industry for films in Akan, the country's most widely spoken language, has also emerged. This industry is located in Kumasi, the country's second-largest city, and is accordingly known as “Kumawood.” At the same time, the emergence of streaming platforms has granted an international audience access to Ghanaian movies for the first time. For example, the film “Potato, Potahto” (2017) by director Shirley Frimpong-Manso, whose puts female characters to the forefront, was temporarily available abroad via Netflix. The film, about a divorced couple who decide to continue cohabitating was shown at the Cannes Film Festival and is an example of modern Ghanaian cinema, which is characterized by higher production quality and contemporary themes.

This small selection hopefully illustrates how diverse Ghana's film landscape is. It has always been intricately connected to Ghana's history and culture. Some of these films can be easily found online after a quick search – so if you're interested, why not give one a watch?